Purchasing a second property elevates an investor into a more complex landscape of tax legislation. This environment extends far beyond the initial purchase price. For any serious international investor, a thorough understanding of the second home tax implications is not merely advisable—it is a fundamental component of due diligence.

These tax obligations should be treated as a core variable in your investment calculations, not an afterthought. Tax regimes vary significantly between jurisdictions, making professional, localised advice an essential prerequisite for building a robust global property portfolio.

Understanding the Global Landscape of Second Home Taxes

Tax authorities worldwide invariably distinguish between a primary residence and a second home. This single distinction introduces a new stratum of financial responsibilities that apply from acquisition through to disposal. For the informed investor, this financial journey has a clear, navigable map.

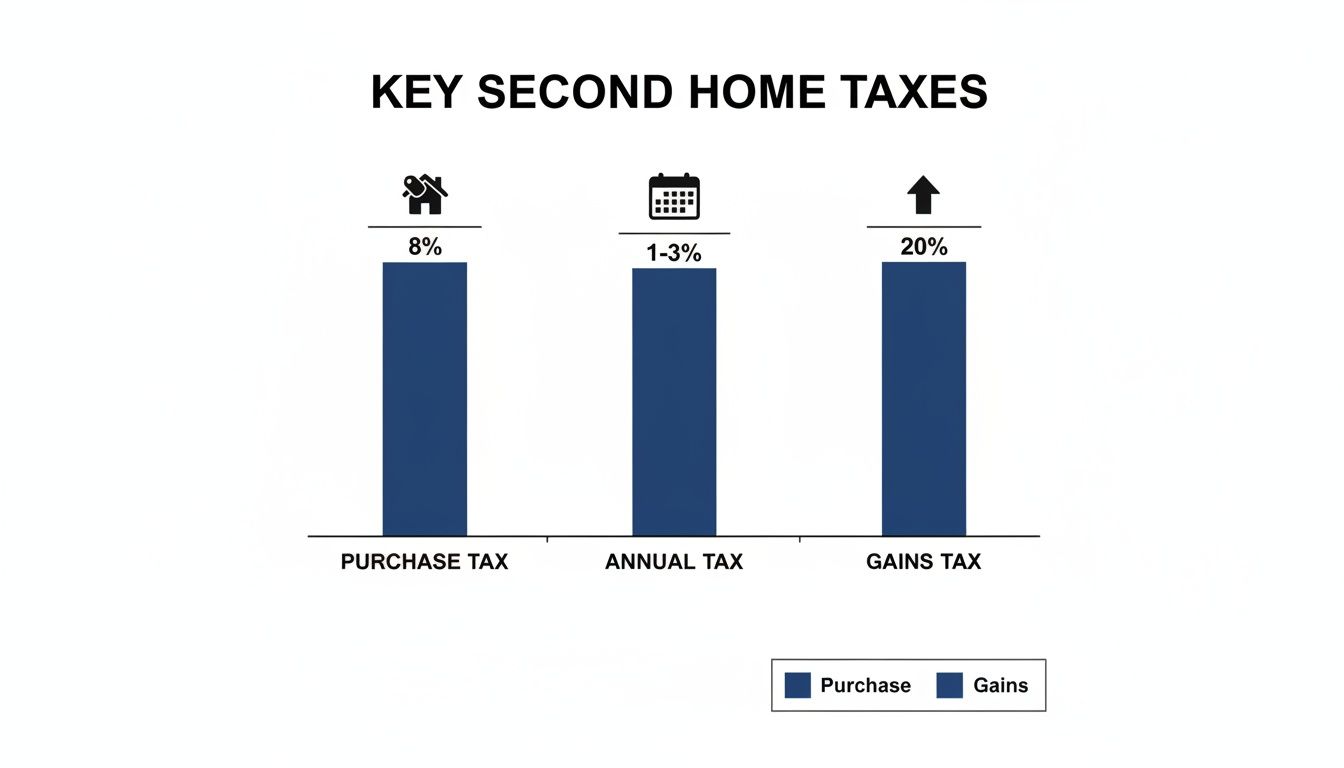

Investors typically encounter three main categories of tax. Firstly, acquisition taxes such as Stamp Duty are one-off charges levied at the point of purchase, which are almost always higher for additional properties. Secondly, annual holding costs, such as property or council taxes, may also attract a premium. Finally, and most critically for calculating returns, are the taxes on rental income and the capital gains realised upon sale.

The Three Pillars of Second Home Taxation

To construct a viable financial model, every potential liability must be accounted for. These liabilities generally fall into three distinct categories:

- Acquisition Taxes: These are significant one-off charges paid at the outset. In the UK, this takes the form of the Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) surcharge. In Spain, it is the Property Transfer Tax (ITP). These upfront costs can add a considerable percentage to the initial capital outlay and must be budgeted for from day one.

- Annual Property Taxes: These are the recurring charges that fund local services. Examples include Council Tax in the UK, the Impuesto sobre Bienes Inmuebles (IBI) in Spain, or Property Tax in the USA. Crucially, in jurisdictions such as the UK, local authorities now possess the power to double these charges for second homes, as confirmed by Gov.uk guidance.

- Income and Capital Gains Taxes: Rental income generated by the property is taxable. Upon disposal, any capital appreciation is subject to Capital Gains Tax (CGT). Unlike a primary residence, a second property rarely qualifies for principal residence exemptions, meaning the entire gain is typically exposed to taxation.

This chart provides a clear illustration of how these core taxes are structured, highlighting the most significant financial impacts over the investment lifecycle.

As shown, acquisition and gains taxes typically represent the largest single payments. Annual taxes, while smaller individually, create a consistent drag on net rental income. A successful investment strategy requires meticulous planning for all three from the very beginning.

To learn more about building a solid financial foundation for your investments, review our comprehensive guide for property investors.

Decoding Acquisition Taxes and Stamp Duty Surcharges

When acquiring a second home, the first material cost is the acquisition tax. This is a one-off government levy on the transaction itself, which can significantly increase the initial cash outlay and directly impact the overall return on investment. For any global investor, a firm grasp of these upfront costs is a critical component of financial planning.

In the UK, this tax is known as Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT). A key element of the second home tax implications is the higher rate of SDLT payable on the purchase of an additional residential property. This surcharge is a fiscal policy tool designed to moderate demand from multiple-property owners and must be factored into any acquisition budget.

How the Stamp Duty Surcharge Works

The higher rate for additional properties is a supplementary tax applied on top of the standard SDLT residential rates. In practical terms, an additional percentage is added to each tax band, making the purchase significantly more expensive than that of a primary residence.

Let's examine a specific example. For a primary residence purchase in the UK, a £350,000 property would attract a standard SDLT liability of £5,000. For a second home, the calculation changes dramatically due to the surcharge. You can review the standard Stamp Duty Land Tax residential property rates on the official government website.

Worked Example: UK Second Home Purchase

- Property Price: £350,000

- Standard SDLT Calculation:

- 0% on the first £250,000 = £0

- 5% on the next £100,000 = £5,000

- Total Standard SDLT = £5,000

- Higher Rate SDLT Calculation (Second Home):

- 3% on the first £250,000 = £7,500

- 8% on the next £100,000 = £8,000

- Total Higher Rate SDLT = £15,500

The surcharge more than triples the tax liability in this scenario, adding an extra £10,500 to the upfront costs. This figure must be built into your financial model. A clear understanding of these costs is vital before proceeding with financing an investment property.

A Global Perspective on Acquisition Taxes

The concept of a higher tax rate for additional properties is not unique to the UK. Many countries employ similar systems to manage their housing markets. The first step for any investor is to understand the local terminology.

- Spain (Established Market): Investors will encounter the Impuesto de Transmisiones Patrimoniales (ITP), a regional transfer tax varying between 6% and 11%. Unlike the UK's tiered system, it is typically a flat rate applied to the purchase price, representing a major initial cost.

- Portugal (Established Market): Portugal’s Imposto Municipal sobre Transmissões Onerosas de Imóveis (IMT) operates on a sliding scale. Rates for second homes are often higher, reaching up to 7.5% on properties valued over €1 million.

- United Arab Emirates (Emerging Market): In Dubai, the Dubai Land Department (DLD) levies a registration fee of 4% of the property value on all transactions. This flat-rate system is simpler than those in many European markets but remains a significant upfront cost.

The key takeaway is that acquisition taxes represent an immediate and substantial cash outlay. Whether it is a tiered surcharge, a high flat rate, or a registration fee, these costs must be budgeted for to avoid undermining the investment's viability from the outset. Always seek local professional advice to confirm the exact rates and regulations.

Understanding Annual Property Taxes and Council Tax Premiums

Once the one-off acquisition taxes are settled, the ongoing cost of second home ownership materialises through annual levies. These recurring taxes are a fundamental component of the financial model, directly impacting holding costs and eroding net rental yields if not properly accounted for.

In the UK, the primary annual charge is Council Tax, a local tax based on a property’s valuation band. Historically, second homes often benefited from discounts, but this policy has been reversed. New legislation now empowers local authorities not only to eliminate discounts but to impose significant premiums.

The Squeeze from Council Tax Premiums

Under the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023, local councils in England can apply a premium of up to 100% on furnished second homes that are not used as a primary residence. This effectively doubles the annual Council Tax bill, a policy explicitly aimed at addressing housing shortages in high-demand areas.

This is not a theoretical risk but a tangible market force. Office for National Statistics (ONS) data indicates a decline in the number of dwellings classified as second homes, a trend directly attributable to tighter tax policies and the rollout of these premiums. Many owners are being forced to re-evaluate their investment strategies.

Real-World Example: The Cornwall Premium

An investor owns a second home in Cornwall, categorised in Council Tax Band E, with a standard annual bill of £2,866. If the local authority applies the full 100% premium, the annual liability increases to £5,732. This additional £2,866 is a direct reduction in the property's net income, impacting the yield calculation.

It is therefore essential to verify the local council’s policy before acquisition. This information, usually available on the council website, can fundamentally alter the financial viability of an investment.

How Annual Property Taxes Work in Other Key Markets

The concept of an annual property tax is universal, although nomenclature and calculation methods vary. Familiarity with local terminology is the first step in international due diligence. You can gain a broader perspective as you understand property taxes across different regions.

- USA (Property Tax): In the United States, property tax is a significant local charge based on the home's assessed value (an 'ad valorem' tax). Rates vary substantially by state and county but typically range from 0.5% to 2.5% of the property’s value annually.

- Spain (IBI Tax): In Spain, owners pay the Impuesto sobre Bienes Inmuebles (IBI). This municipal tax is calculated on the property's rateable value (valor catastral), set by the town hall. Rates generally fall between 0.4% and 1.1%.

- France (Taxe Foncière): French property owners are liable for the taxe foncière, a land tax based on the property’s theoretical rental value. It is payable by the owner as of 1st January, irrespective of occupancy status.

For the global investor, these annual taxes are not minor details; they are a core operational expense. Failure to account for them accurately will result in overestimated profits and potential cash flow challenges.

Calculating Tax on Rental Income and Capital Gains

For most investors, a second home is an income-producing asset. To determine its true return, one must analyse how both its rental income and eventual sale proceeds are taxed. Both revenue streams are subject to scrutiny by tax authorities.

Once a property generates rental income, that income becomes taxable. While the specific rules differ between established markets like the UK and emerging economies, the fundamental principle is consistent: tax is levied on profit, not gross revenue. This distinction is critical, as it permits the deduction of legitimate expenses.

Understanding Tax on Rental Income

The process begins by calculating the total rental income received within a tax year. From this gross figure, a range of “allowable expenses”—costs incurred wholly and exclusively for the purpose of letting the property—can be subtracted. Meticulous record-keeping is therefore essential for legally minimising the tax liability.

Common deductible expenses include:

- Direct Running Costs: Letting agent and property management fees, accountancy fees, and buildings and contents insurance.

- Maintenance and Repairs: The cost of general upkeep is deductible, such as redecorating between tenancies or repairing fixtures. This does not include capital improvements that enhance the property's value, such as adding an extension.

- Utility Bills and Council Tax: If these costs are borne by the landlord rather than the tenant, they can be offset against rental income.

It is crucial to note that rules regarding mortgage interest relief have been reformed in many countries. In the UK, for instance, individual landlords can no longer deduct mortgage interest as a standard business expense. Instead, they receive a tax credit equivalent to 20% of their interest payments—a significantly less generous provision for higher-rate taxpayers.

The resulting figure after deductions is the net rental profit. This amount is added to the investor's other income and taxed at their marginal income tax rate. For non-resident landlords, tax is often handled through withholding schemes.

Calculating Capital Gains Tax on Sale

Upon selling a second home, investors face another significant tax event: Capital Gains Tax (CGT). This is a tax on the profit, or 'gain', realised from the disposal of an asset that has appreciated in value. A firm understanding of CGT is a critical part of the second home tax implications that will define any exit strategy.

The taxable gain is not simply the sale price. It is the sale price less the ‘cost base’, which comprises the original purchase price plus acquisition costs like Stamp Duty and legal fees. Critically, the cost of major capital improvements made during ownership can also be added to this base.

Worked Example: Calculating a Capital Gain

- An investor acquires a second home for £250,000. Associated buying costs (Stamp Duty, legal fees) are £15,000.

- Five years later, a new kitchen is installed for £10,000.

- The property is sold for £350,000, with selling costs (agent fees) of £5,000.

- Cost Base: £250,000 + £15,000 + £10,000 = £275,000.

- Taxable Gain: (£350,000 – £5,000) – £275,000 = £70,000.

This £70,000 gain is the amount on which Capital Gains Tax is payable. In the UK, the CGT rates for residential property are higher than for other assets, currently set at 18% for basic-rate taxpayers and 28% for higher-rate taxpayers.

The most important distinction is the absence of Private Residence Relief (PRR). This valuable exemption typically shields the sale of a main home from CGT. As this relief does not apply to second homes, any gain is fully exposed to tax, making strategic planning essential.

Managing Cross-Border Tax and Double Taxation Treaties

For the global property investor, tax obligations are rarely confined by national borders. Owning a second home abroad introduces a layer of complexity, as accountability extends to multiple tax authorities. This cross-border dimension is a crucial element in understanding the complete tax implications of a second home.

Generating rental income from a property in a foreign country almost invariably creates a local tax liability. This is a fundamental principle of international tax: sovereign nations have the right to tax income generated within their territory, irrespective of the property owner's residence. A UK resident with a rental property in Spain must therefore declare that income to the Spanish tax authorities and pay tax locally.

This raises a critical issue for any investor: the risk of being taxed twice on the same income. This is where Double Taxation Agreements (DTAs) become an indispensable financial tool.

The Role of Double Taxation Agreements

A Double Taxation Agreement, or treaty, is a formal accord between two countries designed to prevent individuals and businesses from being taxed on the same income or gains in both jurisdictions. The UK, for example, maintains one of the world's most extensive DTA networks, with agreements covering over 130 countries.

These treaties establish rules to determine which country has the primary right to tax specific types of income. For property income, the rule is almost universally that the country where the property is located has the first right to tax.

The DTA then provides a mechanism, typically a tax credit, to ensure the tax paid abroad can be offset against the home country’s tax bill on the same income. This prevents punitive double taxation on international investments.

Example: UK Resident with a Spanish Property

- A UK tax resident owns an apartment in Marbella, Spain, generating £10,000 in net rental profit.

- Spain taxes this income first, at a non-resident rate of 19%, resulting in a Spanish tax liability of £1,900.

- As a UK resident, this £10,000 must also be declared on their UK tax return. If the investor is a higher-rate taxpayer (40%), their UK tax liability on this income would be £4,000.

- Under the UK-Spain DTA, the investor can claim Foreign Tax Credit Relief for the £1,900 already paid in Spain. This credit is deducted from their UK bill, leaving a residual payment of £2,100 (£4,000 – £1,900) to HMRC. The total tax paid is £4,000, aligning with their UK marginal rate and avoiding double taxation.

Defining Your Tax Residency

The concept underpinning international tax is tax residency. An individual's country of tax residence is where their primary fiscal obligations lie and where they are typically taxed on their worldwide income and gains.

Determining tax residency is not always straightforward. While rules vary, a common international benchmark is the 183-day rule: spending more than 183 days in a country during its tax year will likely establish tax residency. Other factors include the location of a permanent home, the centre of vital economic interests, and habitual abode.

Correctly establishing residency status is paramount. It dictates which country has the right to tax worldwide assets versus which can only tax locally sourced income. For investors with a multi-jurisdictional portfolio, navigating these rules is essential for compliant and efficient tax planning. Our guide on investing in overseas property offers further insights. Errors can lead to significant financial penalties.

Strategic Tax Planning for Second Home Owners

Understanding tax liabilities is the first step; actively managing them to protect returns is the next. Effective tax planning is not about tax avoidance but about structuring an investment in the most efficient and compliant manner from the outset. This can significantly reduce the overall tax burden over the asset's lifecycle, influencing everything from annual cash flow to the net profit realised on disposal.

Informed decisions must be made prior to acquisition. A fundamental choice, such as the ownership structure, can have profound long-term tax consequences.

Choosing the Right Ownership Structure

One of the most critical decisions is whether to hold the property personally or through a corporate entity, such as a limited company. Each structure carries a distinct set of tax implications.

- Individual Ownership: This is the most direct method. Rental profits are added to personal income and taxed at the individual's marginal rate. However, as seen in the UK, mortgage interest relief for individuals is restricted to a 20% tax credit, a significant disadvantage for higher-rate taxpayers.

- Limited Company Ownership: Holding the property within a company subjects rental profits to Corporation Tax, which is often lower than higher-rate income tax. The company can also typically deduct the full amount of mortgage interest as a legitimate business expense. The drawback is that extracting profits from the company, usually via dividends, incurs further personal tax liabilities.

Timing and Documentation Strategies

Beyond ownership structure, effective asset management can yield significant tax savings. This relies on two core principles: meticulous record-keeping and strategic timing.

A common strategy involves timing a disposal to maximise the use of the annual Capital Gains Tax (CGT) allowance. This tax-free threshold resets each year. By selling in a tax year where the allowance has not been otherwise utilised, a portion of the gain can be shielded from tax.

Key Takeaway: The most effective defence against an excessive tax liability is robust documentation. Maintain detailed records of all capital improvements—such as a new extension or a significant renovation. These costs can be added to the property's "cost base," which directly reduces the taxable gain upon sale.

A Practical Checklist for Tax Optimisation

A structured approach is essential for effective management. This checklist outlines the key stages of the investment journey.

- Pre-Purchase Diligence: Conduct thorough research on the local tax regime before acquisition. Ascertain exposure to wealth taxes and evaluate the tax treatment of a limited company in that jurisdiction.

- Ongoing Record-Keeping: Maintain precise records of all income and every allowable expense. This includes letting agent fees, repair bills, and other operational costs to ensure all legitimate deductions are claimed.

- Capital Improvements Log: Systematically file all invoices for major works that enhance the property's value. This documentation is invaluable for reducing a future CGT liability.

- Seek Professional Advice: Engage a cross-border tax advisor before making any significant decisions. Their specialist expertise is crucial for developing a strategy that aligns with your objectives and ensures compliance across all relevant jurisdictions.

Navigating the complexities of second home tax implications requires diligence. For further insights into structuring investments, explore the broader strategies discussed in our property investment section.

Frequently Asked Questions About Second Home Taxes

When examining the specifics of second home taxation, several questions consistently arise. Here are concise, practical answers to the most common queries from global investors.

Do I Pay Capital Gains Tax on a Second Home If I Make No Profit?

No. Capital Gains Tax (CGT) is levied only on the profit—the ‘gain’—realised from the sale of an asset. If no profit is made, no CGT is due.

The gain is calculated by subtracting the ‘cost base’ from the final selling price. The cost base includes the original purchase price, associated acquisition costs (e.g., stamp duty, legal fees), and the cost of any capital improvements made during ownership. If this calculation results in a break-even figure or a loss, there is no CGT liability. Furthermore, most jurisdictions provide an annual tax-free CGT allowance, meaning tax is only paid on gains exceeding this threshold.

How Does Owning a Second Home Abroad Affect My Home Country Tax Filings?

Owning property abroad will almost certainly create tax obligations in both countries. If you are a UK tax resident, for example, you are liable for tax on your worldwide income and gains. This requires you to declare any rental income and capital gains from a foreign property on your UK Self-Assessment tax return.

Double Taxation Agreements are in place to prevent income from being taxed twice. These treaties allow you to claim a credit for taxes paid in the country where the property is located. This credit is then offset against your UK tax liability. The key is to ensure full compliance with reporting requirements in both jurisdictions.

Can I Reduce My Council Tax Bill on an Empty Second Home?

This is highly unlikely. The current policy trend is to penalise, not incentivise, the ownership of empty second homes. While some historic discounts for unfurnished properties may have existed, these have been largely phased out in favour of premiums.

Local authorities in England, for instance, now have the power to charge a premium of up to 100% on second homes. This doubles the council tax bill, regardless of whether the property is occupied. Higher premiums often apply to properties left empty long-term. Leaving a second home empty is an increasingly costly strategy and must be carefully factored into holding cost calculations.

Ready to compare markets and make your next move? At World Property Investor, we provide the in-depth guides and data-driven analysis you need to invest with confidence. Explore global opportunities today at https://www.worldpropertyinvestor.com.